The following excerpt struck me as having helpful critical implications for "The Emerging Church" movement, so well-intentioned and prevalent here in the evangelical wings of the C of E.

Would that all "contemporary" churches held themselves to such a line of thought as the following one espoused by Herr Moltmann! I fear that too many Anglicans (and all denoms with an established theological tradition) are neglecting the advantages their theological roots afford them. For example, the Book of Common Prayer oozes theological and pastoral insight!

In England many have chucked liturgy, the understanding being that its absence is the first ingredient necessary for church (re)growth. Liturgy seems to be associated with Imperialism and slavery, or something like that. On the other hand, in the States, many of us adore liturgy for exactly the opposite (wrong) reasons: We think it makes church seem more legitimate, and less ignorant / naive than the less worldly non-denominational alternatives down the street. Such a caricature epitomizes the make-up of most ECUSA congregations in NYC. Oxford is an even more obvious example of the same thing. It is a place where Americans specialize in exactly that kind of insecurity. I've just come from an Alister McGrath debate at the University Student Union, and over half of the questions from the floor came from Americans! English culture, which is pretty depressing by the way, cannot quell such deep need for affirmation. I feel for my fellow American seminarians who have come all the way to England, the supposed Mother Ship of Anglicanism, only to find the most casual, insubstantial churches they've ever seen, churches where the clergy are eager to hear whether or not you have ever been to Willow Creek, Time Square Church, and the Kansas City Prophet place? You can almost hear these poor Episcopalians muttering under their breath, "You mean the Canterbury Trail ends here?..."

The common line (one of Nicky Gumbel's) is that the church must "keep the message, but change the packaging". Unfortunately, I have yet to find one church that has re-packaged without changing the message, theology, and ecclesiology. The first thing to go seems to be any doctrine of sin as total depravity. To the extent that these Christian estimations of human anthropology slighten that doctrine, the Cross is robbed of exactly that much power. The result is always the same poll-vault over Calvary, a place where, given Easter, morality and churchiness as the content of the Christian faith are preached, or, rather, taught. Christianity of this ilk always becomes what I would call "flaky", either overly glory-based or overly mystical in its leanings. I've heard that, in Sydney, they've done a wonderful job of translating the BCP into intelligibly accessible language without losing the pith. To my way of thinking, that sounds like the right initial approach.

But the fact that much of the evangelical Church is totally consumed with being "Radical" (California-Teenage-Mutant-Ninja-Turtle style) and "culturally relevant" displays the extent to which the (actually) radical Christian Gospel has lost its primary seat in Church. We're right to take the criticism of having been overly aloof and obtuse, too far removed from the reality of human anxiety in the day-to-day. I agree. We need to stop painting clownish smiles on frowning faces, while guilt funnels its tithe directly into the Youth Program in hopes that "at least the children will experience Grace".

But the fact that much of the evangelical Church is totally consumed with being "Radical" (California-Teenage-Mutant-Ninja-Turtle style) and "culturally relevant" displays the extent to which the (actually) radical Christian Gospel has lost its primary seat in Church. We're right to take the criticism of having been overly aloof and obtuse, too far removed from the reality of human anxiety in the day-to-day. I agree. We need to stop painting clownish smiles on frowning faces, while guilt funnels its tithe directly into the Youth Program in hopes that "at least the children will experience Grace". But let's not necessarily think the problem has been a lack of arcade games in the nave, or that of contemporary-worship-leader "sincerity" (don't even get me started on the flute-playing a la Herbie Mann, though without the shirt off, which would be an improvement, for that matter). Suddenly Sunday church services are being modeled after their own Youth Groups!

What I want to know is, since when has critiquing the secular world's humanistic, Pelagian thinking not sounded radical and relevant? Or is that practise now completely out of vogue except maybe via Paul Walker, Tim Keller, and / or that Terryl Glenn (?) guy at the AMIA flagship on Paulie's Island? Fortunately, Cranmer does it ad infinitum, and, these days, Sunday evenings find me making a bee-line for what is arguably Oxford's most pathetic traditional sung Evensong, where I get the Gospel I crave straight out of the Book of Common Prayer. Only a God of Grace would show up in that service, and He does!

I say, first, start preaching the Gospel again as described in antiquated Article 11: "The justification of man -We are accounted righteous before God solely on account of the merit of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ through faith and not on account of our own good works or of what we deserve. Consequently the teaching that we are justified by faith alone is a most wholesome and comforting doctrine. This is taught more fully in the homily on Justification." Preach it again and again (like a broken record for consistently broken lives)! Preach it to Christian and non-Christian sinners alike! Preach it like you're Augustine and they're Pelagius. Just as G. Forde says, "let that bird fly!" Those that can hear it will lap it up (yes, I believe in Irresistible Grace), for it is a / (THE) "most wholesome and comforting doctrine". It is sufficient.

Suddenly, good old-fashioned Parish ministry looks pretty radical to me. I can't wait! -- JAZ

p.s., Along similar lines, I like Luther's first thesis of his famous 95, where he basically says the following: "When Jesus said 'Repent and Believe' (because the latter is contingent upon the former), he meant that the entire Christian life should be made up of 'Repenting' (and, thereby, 'Believing')." As far as I'm concerned, it's a pretty good model.

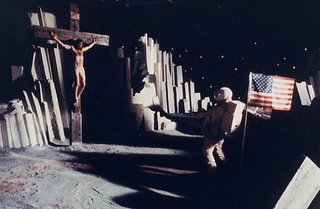

p.p.s., As far as church for the post-modern world goes, I've never seen a better model than the one offered in John Ford's 'Donovan's Reef' (1963). In the movie, we find a church community gathered on Christmas Eve, in Hawaii, during a severe rain storm. A seemingly traditional, children's Christmas pageant begins. The congregation, which includes John Wayne (!), sits (each holding a candle), in their most formal, floral-printed shirts and muumuus, singing Silent Night in traditional Hawaiian tongue. On the stage, the setting is much the same as one might imagine, a small manger, children dressed as angels, and the narrator reads from the beginning of Luke. Only, in introducing the Magi, the wise men are entitled: The Prince of Polynesia, The Emperor of China, and The King of the United States of America. Instead of baring gifts of frankincense, gold and myrrh, the Polynesian, clad in loin cloth and tropical wreath, carries a platter full of pineapples, the Emperor of China brings a tray of different teas, and the King of the USA, strangely enough, carries a phonograph and wears a crooked crown. The scene is peculiar and the “same old story” has vibrancy, and renewed power. Yet the elements include an old German hymn translated into Hawaiian, an old story retold with modern elements (pineapples and a phonograph), an ethnically diverse congregation, children and adults, etc. Truly postmodern! And its poignancy still brings tears to the eyes. This photo of the astronaut on the moon, worshipping the Cross is another favorite image of mine for similar reasons.

p.p.s., As far as church for the post-modern world goes, I've never seen a better model than the one offered in John Ford's 'Donovan's Reef' (1963). In the movie, we find a church community gathered on Christmas Eve, in Hawaii, during a severe rain storm. A seemingly traditional, children's Christmas pageant begins. The congregation, which includes John Wayne (!), sits (each holding a candle), in their most formal, floral-printed shirts and muumuus, singing Silent Night in traditional Hawaiian tongue. On the stage, the setting is much the same as one might imagine, a small manger, children dressed as angels, and the narrator reads from the beginning of Luke. Only, in introducing the Magi, the wise men are entitled: The Prince of Polynesia, The Emperor of China, and The King of the United States of America. Instead of baring gifts of frankincense, gold and myrrh, the Polynesian, clad in loin cloth and tropical wreath, carries a platter full of pineapples, the Emperor of China brings a tray of different teas, and the King of the USA, strangely enough, carries a phonograph and wears a crooked crown. The scene is peculiar and the “same old story” has vibrancy, and renewed power. Yet the elements include an old German hymn translated into Hawaiian, an old story retold with modern elements (pineapples and a phonograph), an ethnically diverse congregation, children and adults, etc. Truly postmodern! And its poignancy still brings tears to the eyes. This photo of the astronaut on the moon, worshipping the Cross is another favorite image of mine for similar reasons.(from The Crucified God) --

"A Christianity which does not measure itself in theology and practice by this criterion of Christ crucified loses its identity and becomes confused with the surrounding world; it becomes the religious fulfilment of the prevailing social interests, or of the interests of those who dominate society. It becomes a chameleon which can no longer be distinguished from the leaves of the tree in which it sits.

"But a Christianity which applies to its theology and practice the criterion of its own fundamental origin cannot remain what it is at the present moment in social, political and psychological terms. It experiences an outward crisis of identity, in which its inherited identification with the desires and interests of the world around it is broken down. It becomes something other than what it imagined itself to be, and what was expected of it.

"To be radical, of course, means to seize a matter at its roots. More radical Christian faith can only mean committing oneself without reserve to the 'crucified God'. This is dangerous. It does not promise the confirmation of one's own conceptions, hopes and good intentions. It promises first of all the pain of repentance and fundamental change. It offers no recipe for success. But it brings a confrontation with the truth. It is not positive and constructive, but is in the first instance critical and destructive. It does not bring man into a better harmony with himself and his environment, but into contradiction with himself and his environment. It does not create a home for him and integrate him into society, but makes him 'homeless' and 'rootless' (yep, we become extra-terrestrials. JZ), and liberates him in following Christ who was homeless and rootless. The 'religion of the cross', if faith on this basis can ever be so called, does not elevate and edify in the usual sense (i.e., in the mystical sense. JZ), but scandalizes; and most of all it scandalizes one's 'co-religionists' in one's own circle. But by this scandal it brings liberation into a world which is not free. For ultimately, in a civilization which is constructed on the principle of achievement and enjoyment (not including the USA. JZ), and therefore makes pain and death a private matter, excluded from its public life, so that in the final issue the world must no longer be experienced as offering resistance, there is nothing so unpopular as for the crucified God to be made a present reality through faith. It alienates alienated men (i.e., it won't allow them to understand themselves as Gods, as having ultimate control. JZ), who have come to terms with alienation. And yet this faith, with its consequences, is capable of setting men free from their cultural illusions, releasing them from the involvements which blind them, and confronting them with the truth of their existenc and their society.

"Before there can be correspondance and agreements between faith and the surrounding world, there must first be the painful demonstration of truth in the midst of untruth. In this pain we experience reality outside ourselves, which we have not made or thought out for ourselves (one of the ways in which liturgy is so helpful! JZ). The pain arouses a love which can no longer be indifferent, but seeks out its opposite (Grace = unmerited love for a sinner. JZ), what is ugly and unworthy of love, in order to love it. This pain breaks down the apathy in which everything is a matter of indiffernece, because every one meets is always the same and familiar.

"Thus the Cross in the church is not just what Christian custom would have imagined...It does not invite thought, but a change of mind. It is a symbol which therefore leads out of the church and out of religious longing into fellowship of the oppressed and abandoned. On the other hand, it is a symbol which call the oppressed and godless into the church and through the church into the fellowship of the crucified God. Where this contradiction in the cross, and its revolution in religious values, is forgotten, the cross ceases to be a symbol and becomes an idol, and no longer invites a revolution in thought, but the end of thought in self-affirmation." (pp. 34-35)

79 comments:

For what it's worth, I find the image of Contemporary Worship as a bad youth group meeting entirely accurate.

The most meaningful worship service I have ever attended took place in the Cathedral of the diocese of Pittsburgh. There's something overwhelming about watching a bishop in his mitre raise his hands in praise to a hymn played on the organ.

It reminds me of the time I was sent old dates that had gone mouldy in the box, they had come from all nations. I said a prayer: shielded from the realities of their ultimate destiny - going straight into the bin. Your piece reminds me of the Marks and Spencers campaign: "Not just food (packaging too)". M&S go mental for packaging - and salt - the salt of the earth in fact.

It's so hard, though, to criticize "contemporary worship" effectively without sounding like an elitist --- People simply will not have it. You are thought to be stuffy, old-fashioned,or stuck-up . I am currently depressed by the occasional Taize worhsip at our evening service and how "psyched" everyone gets because it's so wonderful and different. (Oh, and also the "liturgical dancing", which is basically one beautiful ballerina, performing). Although I try to understand and "feel" the worship, it is very difficult. Instead, it brings out every bit of my cynicism and meanness toward ECUSA, the people planning the 5:00, popular culture, etc. etc.

I particularly like the placement of the Amercian flag behind the astronaut in that picture.

I agree with john's diagnosis, but not fully. I think every change in worship style is in reaction to something that preceded it. The contemporary movement came in reaction to the liturgical/traditional worship that was too "stuffy", too "anal", too "heady". When contemporary worship has run out of juice, we react again and we go back to liturgy (or something that's a syntehsis of the old liturgical practice, but maybe with "relevant" preaching in the service.) If traditional liturgical service is to return, I'll give it 15 years before we move onto contemporary service again.

The story of history is such: thesis, antithesis, synthesis. The history of classical music is such. Now we are in an age where orchestral music is atonal. 3 minutes of silence in the orchestra, leaving only the sound of audience shifting, flipping their program, etc. is a concert performance.

The Spirit moves where it wills, be that in contemporary or traditional worship.

P.S. I think a fair criticism would be that contemporary worship often neglects the Cross, but it is the neglection, not the worship style, that is to be criticized.

However, whether contemporary worship is conducive or a hinderance to communicating the Cross is another matter.

Well said, JZ.

I wonder when Sunday worship was ever NOT liturgical? As far as I know, it was liturgical (and Eucharistic) as far back as we have any record. It's liturgical and Eucharistic, i.e., in the first century (cf. Didache and Ignatius). As far as I can tell, liturgy was the rule for corporate Christian prayer (except, perhaps, among the most radically "reformed" bodies -- e.g. Quakers and Anabaptists) until about the 1960's. Liturgy has certainly been the consistent rule among Anglicans -- even among the Puritan-minded.

Dear John,

(I just love beginning letters like that!). Even after three years of seminary, I still have questions that I should know the answers too, but alas, there's too much odd stuff floatin' around up there.

Because I'm a recent Calvinist (more of a Lutheran variety, actually) when it comes to grace/election, I'm not sure how to handle questions by parishoners about Irresistable Grace. My wife has been struggling with this too, for certainly "God wants all to be saved."

For example, I had a woman come up to me to discuss what I had said at a Bible Study, and she claimed that there were many times when she felt God calling her, but she kept (and was able) to resist his calling. She was able, by her own will, to deny God's plan for her.

What do we make of this?

I would love any of your thoughts.

Worship at the time of the Acts of the Apostles were not liturgical!

Don't get me wrong--I'm not anti-liturgy--and certainly, living in Cambridge makes me realize how the church is totally lacking in the Gospel. I do think there is some truth to the emerging church in that its rise was, in part, due to the fact that other forms of worship were not cutting it for some folks. Every new thing is a reaction to and synthesis with the old.

Okay, that post by cwytiu is actually me. My name is Word Verification.

Ethanasius, in response to your question, I have also had the same experience. I was called to start a children's ministry in Kosovo that I just didn't want to do. I had always done children's ministry in missions and I was tired of it - I wanted to do something more grown up! So I paced about 10 times around the park where the kids (whom I was supposed to approach) played marbles and argued with God. In the end, I couldn't *not* do what was asked of me, and it was the best thing I could've done for those 18 kids who gave their hearts to Jesus before we left the city.

I would say that if she really felt called, and if it was really God's will for her to enter into that calling, she would really have done it. If she could resist it, and sustain the resistance, it would not have been God's plan, because His will is unstoppable.

Dear Ethanaseus,

I love irresistable grace, can't help but do.

I'm convinced that it is a very important doctrine, helpful in better understanding the nature of grace as revolutionary, that it actually changes things. I don't hold with those who doubt the cheesey good old power of love to affect a change of heart. When one receives love, they cannot resist it. It is like a reflex. Those that kick and scream still in sense believe that they can, in some sense, "pull it off" on their own. They have not really heard the Gospel, which knows they can't and proclaims He has. They are like the alcoholic, unconvinced of their own alcoholism who needs, more than sobriety, to drink more, than he might the better understand the true powerless nature of his/her malady.

A person cannot actually hear of God's love for them as found in Jesus without responding in the affirmative. But that always starts with Sin, not God. Really I think that ministry to the world starts with a diagnosis of sin, not a proclomation of salvation. I like C. F. Walther on that stuff a lot. He writes of Lutheran theology at its most powerfully pastoral. (Also, it's on this point that Barth messes everything up. -- please don't let this comment be the thing with which this discussion gets take up. Let's deal with Irresistable Grace and / or emerging church and liturgy questions. I'm sure anti-Barthian sentiment will resurface again soon)

That said, I think many are not able to hear. Let those who have ears to hear, hear. I think of scales over eyes as another good biblical analogy. Those things are, I believe, really of the devil. The interesting thing about the seed sown parable is that the seed is sown across the board in all places without calculations made afore based on soil tests and lack of shade. I think we are really called to pray that the Holy Spirit will open ears and eyes (hearts, really). It seems that all who call on the name of Jesus will not be exluded, so we are to sow, sow, sow, which we do in the context of drawing out the reality of need (given the omni-present elements of anxiety, anger, and Pelagian attempts to muster glory through achievement), to which only the Gospel of a God who justifies sinners will prove an antidote.

Personally, in the context of preaching I think we are thus called to try to open the hearts of those listening in such a way that the Gospel can be heard. Jesus came for the sick, right? He supped with sinners? Are we not all sick? Who can throw the first stone? Who is perfect as our father in heaven? But how do we draw this out? The Law serves that purpose wonderfully of exposing need. In the extent to which we understand our need for an advocate, not in particular, but as imputed atop our rebellious ontology. I think in 1 or 2 Timothy it mentions that the devil blinds those who are perishing. Well, I believe it, and can't account for the inability of so many to connect the dots, and that I was able to see. That's what I believe, literally.

The lady who says she has refused consciously has not actually heard the Gospel. she may have heard about Jesus, but not in an atoning sense that applies to the reality of her own attempts to stay on the throne through decision-making, careful planning and accountability, etc. She knows not her sickness. Despair, in this sense, is really repentance, the longing for a savior, a ransom. But making someone aware of their need for Jesus (Pascal coined the term "God-shaped whole" in this regard) is ultimately the work of the spirit, not the work of man based on strict adherance to formula or doctrine.

I know what I've said is not witty. I don't think what I'm saying here is at all new-fangled, but I hope it helps. thanks for sharing your experience. I think the alcoholic analogy is a good one. Best, JZ

Bonnie,

The only thing worse than a contemporary worship service in which the spirit is not present is a liturgical service in which the spirit is not present. I attended choral evensong at the parish church here in Cambridge on Sunday, and, aside from an increased hope that Christ would return immediately, I experienced no indication that God was remotely involved. At least no one performing a contemporary worship service is stupid enough to believe that attending "just for the beauty" is acceptible. Makes me want to vomit.

That being said, I attended an instructed eucharist at the highest Anglo-Catholic parish in Boston two weeks ago. Very quickly I realized the way in which the form of worship that emerged among a group of people meeting in houses could be solidified. Imagine the terror that occurred when the last of the Apostles died and Christ had not yet returned. I would make certain the "liturgy" they enacted did not change in the least, for fear of losing contact with the substance of that worship. Experience is a long-enough-term indicator to prove that form and substance will ALWAYS be confused sooner or later.

A young housewife was busy cutting the first three inches off the Thanksgiving turkey before sticking it in the oven. Her husband, dumbfounded, asked what on earth she was doing. She explained that the front of the turkey was bad and needed to be desposed of. He didn't believe her, so they called her mother, who confirmed her assertion. "Where on EARTH did you get such an idea?" the young husband asked his mother-in-law. She insisted that her own mother had maintained the danger of the turkey's first three inches. Finally, all involved agreed to call the grandmother.

"The first three inches are bad? Of course not! I just never owned a pan large enough to fit the turkey in without cutting off three inches!"

Form ALWAYS becomes substance.

Thanks, John, for your very helpful response. I suppose that if we buy that, though, we must also buy Limited Atonement. That's the one that freaks me out. I don't know if I can go there, but perhaps I must. Hope this doesn't again change the subject too much.

Jeff,

Gotcha. My only concern is, how the Gospel (without all the liturgy) is communicated in worship in places where there is no liturgy and/or no literacy. Global missions is the problem that liturgy and "traditional worship" runs into.

I once told Simeon that I didn't like liturgy because it was too verbal; it made me have to think too much, and as such, tired me out.

I wonder if it is not worship that we should criticize, or even FORM, but the preaching. If preaching is bad, people will always rely on the worship and it will take primacy. Then you do run into the problematic Contemporary Bad Youth Group Service. If the preaching is good, the Word of God is always primary, and would have a primary effect. Worship, and even the form of it, should be secondary.

Look at the Bible - worship was worship, not preaching. We now equate the two because they occur in the same place, in the same 1 1/2 hours that we're there, on the same day of every week. Look at David's worship--it was all praise, and praise from his heart. Listening to (okay, reading!) David's praise is not the same as the Gospel, though we see the Gospel worked out in his praise. Worship was never meant to replace the preaching. It's when preaching has gone bad that worship (the secondary thing) becomes primary.

Bonnie,

This is actually the reason why I maintain that the eucharist should be performed at every service.

When you visit Notre Dame de Paris, you'll notice that the choir screen depicts the life of Christ along the right-hand transcept, and the resurrection of Christ along the left-hand transcept. The death of Christ is not depicted, which seems curious at first.

This is not a mistake, however. The death of Christ was the event that tied the two screens together. It was not depicted because, in the Mass, it was to be reenacted.

Luther's critique of sacramental practices in the medieval church is important and well-taken. The problem, however, is that the alternative is equally imperfect. That is, no one is saved by the objectively powerful elements, but, also, no one is saved by the objectively powerful sermon.

The unfortunate truth is that most preaching is just plain bad. A significant portion of ministers don't understand the Gospel at all, and their sermons are very clear indications.

My blockmate's grandfather died during sophomore spring. He was devestation and concerned about the afterlife. HE came to ME and asked if he could come to church with me. The sermon was about godly dating, and my blockmate has not been to church since.

John made a very important and valid point about the eucharist earlier. No matter how awful and heretical the sermon may be, the eucharist service can focus attention away from the life of Christ (where liberals found their "social gospel ministry") and away from the resurrection of Christ (where evangelicals found their "health and wealth gospel") and squarely on the only thing that matters: our Saviour Jesus Christ, who suffered death upon the cross for our redemption; who made there by his one oblation of himself once offered a full, perfect and sufficient sacrifice, oblation and satisfaction for the sins of the whole world.

"That is, no one is saved by the objectively powerful elements, but, also, no one is saved by the objectively powerful sermon.

The unfortunate truth is that most preaching is just plain bad. A significant portion of ministers don't understand the Gospel at all, and their sermons are very clear indications."

Good point! :)

I don't disagree with you on that second point about the poor quality of sermons either. I don't think I have heard a good one since, hmm, Paul Zahl's after our wedding. I do, however, think a powerful sermon teaches what the Eucharist re-enacts. (Simeon, do you get my drift?) The sermon ought to 1) highlight our sin; 2) show us our helplessness and paralysis in attempt to change that situation; and 3) give us hope in Christ Jesus crucified.

Maybe it is a personal thing. When we say the prayers and queue up to receive the bread and wine, I have never been brought to my knees in awareness of my weaknesses, my need for Jesus, and his saving grace during Communion (not in a liturgical Communion service, and not in a traditional/ charismatic service.) I don't know why! Sometimes I'm more worried that I'm going to trip over something, slip on the stone floor and fall over, or do some other awkward thing. It is a solemn moment, I know, but I find it hard to focus on the Cross when I have to make sure I'm doing and saying everything right.

(P.S. I still don't know how to say the grace or the peace or whatever it is that you say at the end of the service!)

Remember, Simeon: don't preach about godly dating at Peterhouse chapel.

Re: Worship in the time of Acts.

And I have nothing against extemporaneous worship, per se. And of course it depends on what one means by "liturgy". I understand it, vaguely, as formal, non-extemporaneous worship.

It is not as obvious to me as it seems to be to you, however, that worship in the time of Acts was not "liturgical" in the above sense. A serious question: If they continued in the Apostle's teaching and fellowship, in the breaking of bread (Eucharist), and in the prayers ---> why the definite article with "prayers" ("tais proseuchais"), unless some Luke means for us to understand a set (i.e. formal) scheme of prayer. Why, in other words, "the prayers" rather than simply "prayer"?

Many discern, likewise, in 1 Corinthians 11 a set Eucharistic liturgical formula: "For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you" -- spoken, as it is, within the context of a discussion of public worship at Corinth.

The liturgy has been, and is, an important way to ensure that our worship is not merely *our* worship, but is in fact the one worship of the Bride, in union with the praise rendered by the Bridegroom, to the glory of the Father, in the power of the Spirit, and in union with the worship of the saints of God in heaven, and the angelic host. One worship, in other words, in union with the love that exists between the three persons of the one God.

Dear Ethanasius,

for what it's worth, no, I'm not into the L in TULIP. It's a problem, while consitent with the implications of certain systematic thought spawned by Calvin (though he never really states "Limited Atonement" in those terms, at least according to A. McGrath, who I'm basically citing on this one), it's not consistent with the bible and the Great Commision. Those who posit limited atonement have to interpret "make disciples of All nations" as suggesting "ALL (TYPES OF) Nations" and stuff like that. That doesn't jive with me. In this sense I'm also single on the predestination tip (coffee Con leche, Sin sucre), and accordingly optimistic, though not to the point that I believe "it is finished" means all people are already saved, or that hell isn't real, or that evil isn't real. I'm just not sweating ministry as being predominantly about teaching morality to Christians, and converting non-believers so that I can teach them about ethics. My church, I guess, will be more like a life boat, or a shelter, rather than like an aerobics class.

Best, John

Jeff and Bonnie,

For what it's worth, I am attending a medium-sized (500 members, one Sunday service) PCA chruch in Asheville these days. It would be so easy for me to list all the aspects of the church that I do and don't like, but really, I keep coming back for one reason: the preacher preaches the gospel. He's a young guy (mid to late 30's?) who is not overly gifted as a speaker, nor is he brimming with charisma (in fact, he is quite humble). But he gets it, and God has placed him at Trinity Pres. in Asheville to proclaim the good news of the risen Christ to sinners. Has he swung and missed a few times? Sure. But most Sundays he is up there speaking, but he's not the one doing the talking. The Holy Spirit is clearly speaking through him. He is connecting with people at their point of real need, helping them to realize their weakenss, anger, and vanity go deeper than they had even realized. And then he brings it back to the Cross. It is a wonderful thing.

We also take Communion after the service every Sunday. I have no problem with this, and I just assumed it was a Presbyterian thing. But two weeks ago he told the congregation that he insists upon it because it serves as a sort of safety net in case he doesn't preach the gospel. At least if the congregation doesn't hear the gospel, they will be reminded of it through reenacting it via the bread and the wine (grape juice). I thought this was great.

On liturgy: It seems that if we define liturgy as non-spontaneous worship, then most services are in fact liturgical. In the Baptist church I grew up in as well as the PCA church I now attend, the service does not vary much week to week. The order remains roughly the same, though the hymns, sermons, readings, prayers, and announcements do change from week to week-- as the do in the Anglican church. I guess what I am saying is that there is still a sense of order. Each person present can look down at the bulletin and see what is going to happen when. I know this is not the exact same as an Anglican or Catholic service, but what is the real difference? Is it just that the Book of Common Prayer makes for a better service than whatever a church ministry team can come up with that week? I suppose it would be different if there were a time in the service for "spontaneous acts as inspired by the movement of the Holy Spirit," but no church I've ever been to has done that (though I'm sure it happens.)

On a side note: Jeff, why must form always become substance, and what implications does this have for different types of church services? I'm not sure I buy it.

Oops, I meant to say that we take Communion after the sermon, not after the service.

John,

I'm sorry about the excursis on the "I" and the "L" of the TULIP. I'm with you, too, I think, when it comes to the L. It just puts a bad taste in my mouth...but I shouldn't be eating tulips anyway.

Is it just a logical incosistency that we have to live with, in denying "L" but uplifting "I"? If it is, I'm ok with it, but I would love to hear your opinion.

Ethan

One more question.

If the love of God, qua grace, is simply irresistible (cue Robert Palmer), and yet not all will be saved, does this not entail that God does not love some? I.e. if he HAD loved them, they would have been unable to resist his love, and would have been saved, right? Maybe this is a naive question, already answered many times over by Calvin (or Luther or somebody), but to be candid, I have never read the Reformers. Shocking, I know. What am I missing?

TG, et alia --

But is ignorance applicable across the board? I.e. if we don't know what the f***s going on, how can we say that grace is irresistible? Or, put the other way around, if we CAN say that grace is irresistible, doesn't that mean that we do in fact know something about what the f*** is going on?

The deep things of God may be inscrutable, but I think I know what it is for something to be irresistible. And those of us who predicate irresistibility to grace, we may presume, take themselves to know what it is for something to be irresistible (otherwise, what basis is there to say that this thing or that thing is irresistible?). And if irresistibility means anything like what I think it means, applying it to God's grace entails that God withholds his (irresistible) grace from a certain set of people -- namely those on whom it is ostensibly inoperative, the damned or whatever you call them.

wb+:

Can you shed some light on what you personally think about the subject of grace? I am having a hard time "reading between the lines" within your posts. And I feel stupid because of it! Throw a brother a bone....

Colton,

Form *must* not become substance (prescriptive) but always *does* become substance (prescriptive).

I defy you to find an Eastern Orthodox priest who will not use a variation of the phrase "continuity with the liturgy of the Apostles" as if that mattered in the least.

Form becomes substance. Why? Human beings are weak and sinful.

Ethanasius,

Although I agree with John about being against limited atonement theologically, for what it's worth, I think that practically speaking, the "L" has to be accepted in theory for one to uphold the "I". Personally, I don't like to use these terms as they have a Calvin/Besa-ish connotation that I run from; nonetheless, it certainly is logically consistent.

Aside from connections with Calvin, the TULIP represents a shift from the pastoral understanding of Justification to a type of protestant scholasticism, which John clearly articulates in his previous post. Nonetheless, I think that if one says that both salvation and sanctification are monergistic then it only makes sense that God, in effect, chooses who will be saved and who will be damned. This is, as they say, a hard teaching.

WB, if you haven't read any of the reformers, you might as well start with Luther and go straight to The Bondage of the Will . In it, Luther expounds on his understanding of the bondage of the human will to sin and its soteriological implications.

Luther was not unaware of the difficulty with his position nor of what it ultimately said about God. On page 101, he writes:

"Now, the highest degree of faith is to believe that He is merciful, though he saves so few and damns so many; to believe that He is just, though of His own will He makes us perforce proper subjects for damnation, and seems (in Erasmus’ words) to delight in the torments of poor wretches and to be a fitter object for hate than for love .

The second "prescriptive" should be a "descriptive".

I just need to shut up and stop proving my ignorance.

I honestly am not sure what I think. Part of the problem is that I don't think in these categories -- TULIP, sola this or sola that. Remember: I haven't read any of the Reformers, and very little contemporary theology. That's not anglo-catholic snoodiness; just the facts.

I've read a good deal of Kierkegaard, who I'm told is in some ways rather lutheran. I like Kierkegaard, particularly "Works of Love." I've read Augustine's anti-Pelagian writings and commentary on Galatians, and honestly found them tedious and uninteresting.

My intuition is that formulae like TULIP (and its components) are efforts at forcing a cohesion on the narrative / historical meaning of Scripture that just isn't there. I think it is cohesive only in the sense first outlined by Origen in De Principiis, where he develops the notion of the various "senses" of Scripture.

And speaking from personal experience, its difficult to discern exactly. But I certainly see the marks of grace on my life leading to what I would call "conversion of heart" which is perhaps an essentially catholic category, corresponding in some respects to a decision for Jesus or some such, preempted by grace. To use Marxist categories: I didn't bring about the material conditions for my decision; God did. That seems clear. But I also think I can make out in my spiritual experience my efforts being rewarded. I.e. the sheer discipline of prayer seems to me to pay dividends.

I have absolutely no doubt about the efficacy of the sacraments in my spiritual life. And I have rarely, if ever, been very moved by any sermon, oddly enough. I can count three profound spiritual experiences (i.e. experiences that I felt powerfully to be overtly spiritual, maybe in a quasi-charismatic sense). Two of them were in the context of the Benediction of the Blessed Sacraments in Roman Catholic churches, and one was while I was praying the Rosary. Take that for what its worth. I tend to be very suspicious of enthusiasm, and I don't think our experience is very important in the long run. In that vein, I rather like what Eric Cadin has said above: that worship is about God's own love for himself, and in the final analysis bears only tangentially on us.

I really don't know. It seems to me like a chicken-egg thing. I really don't know quite what to make about the Justification / Sanctification debates. Nor even how to understand questions like "Are you saved?". The latter seems to assume a narrow, reductive (and for that matter unbiblical) account of salvation.

I mean, I only know what I know, so to speak. And that is to pray and to remember God. And that means, most fundamentally, the sacrifice of Christ. And that means Eucharist, "a perpetual memory of that his precious death and sacrifice, until his coming again." Salvation, practically, in my life, seems to be for me to marinate in the Word of God, and to pattern my life sacramentally (they are the same thing). And I suppose that's why Paul's phrase "being saved" resonates with me. It happens twice. The first time it is about the cross, which is folly to those who are perishing, but to us, who are being saved, the power of God. The second time Paul says "we are the aroma of Christ to God among those who are being saved and among those who are perishing."

So I don't know. Its all about coming to smell like Jesus.

But this ambiguousness is in Paul too. The two big proof texts are ambiguous. "by grace you have been saved through faith... for good works," and "work out your own salvation with fear and trembling, for God is at work in you." Chicken / egg.

Sorry. That was longer than I meant for it to be. Now its time for Evensong.

For those interested, I've just added a few sentences to the fourth paragraph. It now reads:

"The common line (one of Nicky Gumbel's) is that the church must "keep the message, but change the packaging". Unfortunately, I have yet to find one church that has re-packaged without changing the message, theology, and ecclesiology. The first thing to go seems to be any doctrine of sin as total depravity. To the extent that these Christian estimations of human anthropology slighten that doctrine, the Cross is robbed of exactly that much power. The result is always the same poll-vault over Calvary, a place where, given Easter, morality and churchiness as the content of the Christian faith are preached, or, rather, taught. Christianity of this ilk always becomes what I would call "flaky", either overly glory-based or overly mystical in its leanings."

Yet one of the most amazing things I have ever seen was the nervous line of people, hundreds of people, standing outside Nicky Gumbel's church last month for the first night of the Alpha course. Christ uses us in our weakness, or works through what is weak, so whatever it was that first prompted them to make that step into the church--maybe the pomo rep of HTB, or the cinema ad for the course--has led them to hear the gospel for the first time! Does the medium really matter? I may be a sucker for the emerging church because God used it to first get my attention (after growing up in an Episcopalian church and school and still unable to define "gospel"), but I give the movement serious props for its evangelism.

I too am a fan of Alpha, but not as teaching. As evangelism, yes, but as church, no. I worked in the Alpha US head-quarters for two years, have led over 10 rounds of Alpha as a leader, used to sell the course, etc. The 15 Alpha talks are mainly meant to provoke discussion (that's in the literature, not something I made up). There's very little Gospel in the talks themselves, just a survey of general Christian doctrine.

The Gospel of Alpha (and let me clarify, when I say Gospel, I mean "justification by faith in Christ" as expressed in the phrase "Christ died for sinners") is found in the table leaders and helpers who are able and willing to listen to the typical secular hum-drum of Alpha guests, which is the content of the hair-balls they need to cough up in order come into a right relationship with God. People come into the Alpha course and find that suddenly for the first time, people are actually listening to them, and have taken an interest in them. That's the power of the course. People need love and they get it. Furthermore, in England, where the course has taken off so significantly, much of the profound appeal comes from the fact that, in England, it's considered a realy big deal to simply invite someone over for dinner. What Englishman would be so rude as to refuse someone who actually had the audacity to invite them to a "dinner." That element has not translated as profoundly in the US. The Gospel is found in Alpha in theological terms in the way that Righteousness is imputed to everyone who walks in the door, no matter what they think, or where they are from, which is wonderful!

But what happens? Those that convert join the church, where they expect more depth of teaching and whatnot. If they don't get it, they leave as fast as more new people can come in (think St. Bart's NYC, formerly the USA's largest Alpha Course, though the church continues to lose numbers). Or how about HTB? Well, they are now starting a seminary, led by Graham Tomlin. Why do you think? Because they are aware of their own theological weaknesses as a church, that too much emphasis has been placed upon experience-based faith, and while it holds up where conversion is concerned, it doesn't last unless the new convert is immediately turned onto evangelism.

My guess it that the charismatic revival in the UK will start to weign without the Gospel. The Holy Spirit has, in some of these places been substituted for the only Enabling word, like nutra-sweet for sugar, and while not insignificant, it will not hold up under the battering winds of a fallen world that crushes glory-based theology.

I realize those are not very popular or necessarily helpful thoughts but I think they do help to clarify the problem of the emerging church that Moltmann's quote is high-lighting.

Also, for what it's worth, one of the main things that kept me leading Alpha tables had to do with the fact that I was single. Alpha is a great way to meet eligable members of the opposite sex! Nicky himself has underscored the fact. His attitude (rightly I think) is that (as they say in AA): "It's not why they come, it's why they stay that matters." JAz

Happy, Happy Birthday to JEFF DEAN!

To weigh in somewhat on the irresistible grace issue:

1) Thanks wb+ (Will, right?) for bringing Robert Palmer into the discussion. How can we discuss irresistibility without Robert Palmer in the background? You beat me to it. “Irresistible”, “Addicted”, “Bad Case of Lovin’ You”—this guy clearly has my kind of anthropology.

2) I’m not sure what I make of the irresistible grace vs. limited atonement issue. My gut is to go with JZ (and Luther?), to take grace to its pastoral conclusions but to plead the fifth somewhat on its systematic ramifications for biblical reasons. I confess I have not read any Calvin or anything else that deals with this stuff.

3) wb+, I feel you on the chicken/ egg problem of grace vs. participation in that grace, but here, again for pastoral reasons, I don’t think we can plead the fifth the same way. This is because there are huge practical and ministerial ramifications in what seems to be the very subtle distinction between semi-Pelagian and “Augustinian” (i.e. late Augustinian) doctrines of grace.

In a one-on-one pastoral context, it is the difference between “just” listening to someone, and trying actively to fix them. It ends up very often feeling, from the object of pastoral ministry’s point of view, like the difference between feeling loved and feeling told that God’s love for them is contingent on their “accepting” it in x y or z contexts, i.e. feeling told that God’s approval is contingent on their decision for or against sin, which is for or against Him. It is also the difference between sermon as pep-talk-with-some-forgiveness-in-the-middle-in-case-it-doesn’t-work, and preaching the Gospel of God’s love for sinners. To put it in terms of the Eucharist, it is the difference between someone expecting their participation in this central part of the life of the church to make them more able not to sin, and their experiencing in it the reality of God’s love for them despite their sin.

You, and others, may disagree with me on this, but I think it holds up. Say when you meet with someone to whom you are ministering one-on-one: try, just once, to withhold advice completely; to refrain from judging them in any way; to listen only, and to ask questions or share information only insofar as it helps them feel more free to open up; to make a point of NOT sharing the scriptures that “deal” with their problem, because they probably already know them anyway (btw I’m sure you have listened gracefully this way before; my point is to do it consciously and see how it goes). I find that the person always feels loved, feels free to be honest with the sin they already know very well is sin, and feels more interested in going to church/ fellowship, not to mention in meeting with you again. In fact, very often they feel they have actually experienced Christ’s love for them for the first time in a while.

My point is that it is remarkable how effective it is for ministry when you actively and lovingly say nothing. My point is also that virtually no one ever ever does this, and that that is because the overwhelming majority of Christians are semi-Pelagian in their doctrine of grace.

(Calvinists, in practice, are exactly the same, though they’ll deny it to their last breath. Just try meeting with a PCA dude who doesn’t try to fix you, who doesn’t make a big point of asking you the “hard questions”, who doesn’t make you feel that your whole relationship with God depends on sexual purity, “accountability”, etc. Their emphasis on the 3rd use of the Law is their trojan horse for semi-Pelagian ministry, and it ends up overwhelming even their supposed belief in predestination—ironically, no evangelists are more heavy-handed than the Reformed! Ok, off my hobby horse).

The point is that one’s view on these issues has drastic effects on how one ministers. Everyone who says it doesn’t (like C.S. Lewis, at least until late in his life) is a semi-Pelagian who has probably never experienced anything different, and has never heard the idea that God’s grace might not need any help or encouragement to produce the fruit the NT describes. Christians always default to semi-Pelagianism, so much so they often do not realize there is a viable alternative (I’m not saying you’re doing this, wb+, just that so many do).

My other point is that the "Augustinian"/ Lutheran/ non-semi-Pelagian method really works! Really, it does!

Bonnie--Your P.S. is exactly right--- it is the neglect of the cross that feels wrong-- it's the elevation of an individual's talents which feels idloatrous in the services that get to me. I have honestly tried to examine what it is about it that bothers me (am I jealous of a beautiful ballerina? Do I wish I could make music that beautifully?) and yes, both of those things may be true, so it may just be my personal sin manifesting itself. I am interested to know, especially from men, if a gorgeous ballerina floating around to Christian music is conducive to worship (other than of her body) or a hindrance. I know to my husband, it is a distraction from worship, though enjoyable. Or is this simply a matter of style?

For those wanting to hear a take on church worship that is perhaps less familiar (it was new to me), check out this post from Cross Theology:

http://allwashedup.blogspot.com/2005/12/justification-by-praise-alone.html

The comments are especially worth reading as Tom Becker help to open the issue up very clearly for those of us non-confessing Lutherans.

It was the comments about liturgical dance that prompted my putting this up.

JZ

Ok, one last thing, and then I'm done for the day, I promise.

Mattie asked a while back what the scriptural backing for the irresistibility of grace is. To some degree, she is right to suspect that it has to do with Romans 9-11, predestination, etc. But I think there is a better answer, though not one that she will like :)

Irresistible grace in my understanding—again, I have not read Calvin and co.—is a conclusion drawn from the radical Pauline polemic against any type of works or “flesh”. As I wrote on the thread below about Jeff Dean’s insight, semi-Pelagian theology sees grace as utterly and profoundly prevenient—i.e. it goes before us and prepares the way in everything, including conversion as well as sanctification, and nothing is possible for the Christian whatsoever without the grace of God intervening and going before. But semi-Pelagianism still holds that, despite its radical prevenience, grace can be meaningfully resisted by the people to whom God extends his grace. In semi-Pelagian Christianity, no work of God’s grace is achieved in us unless we first consent to it. God makes the consent 100, 000+ times easier through prevenient grace, but he still requires our consent (and therefore our participation) in order to do anything, or else grace would be irresistible. So there is an irreducible “decisional” element in semi-Pelagianism. There is an irreducible reliance on the human will. No matter how minor a role the will plays, it still always plays a role. Otherwise, God’s grace would be irresistible.

The problem for me is that that minute-but-significant reliance on the human will to “acquiesce” to grace is indistinguishable, in practice, from what Paul calls “works”. It is a “work”, a NECESSARY work, albeit a tiny minor one. Without that irreducible “me” element, God cannot save me. Therefore my salvation depends on me. It depends a lot more on God, but it still depends also on me, and that fact, again, is irreducible.

Paul never locates a compromise between human works and God’s work, our efforts and his Effort. For him they are always in radical opposition. “Did you receive the Spirit by works of the law or by hearing with faith? Are you so foolish? Having begun by the Spirit, are you now being perfected by the flesh?” (Gal. 3:2-3); “For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast” (Eph. 2:8-9). “For by works of the law no one will be justified in his sight…For we hold that one is justified by faith apart from works of the law” (Romans 3:20, 28); “Now to the one who works, his wages are not counted as a gift but as his due. And to the one who does not work but trusts him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is counted as righteousness” (Rm. 4:4-5). Always the stress is on the radical opposition between grace and works of the law.

And lest we say that “works of the law” is fundamentally different from simply human effort to do good and act righteously, in Romans 9:30-32 Paul directly equates works with pursuing righteousness of any kind, full-stop: the “Gentiles who DID NOT PURSUE RIGHTEOUSNESS have attained it, that is, a righteousness that is by faith” (Rom. 9:30).

Likewise in John, the action of God and the actions of men are understood to be in radical opposition: “In this is love, not that we have loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins” (I John 4:10).

The question, of course, put very simply, is whether “faith” is a work. Obviously, based on the texts, it can’t be. But the semi-Pelagian view sees faith (and “hearing with faith”) as based on a decision on our part not to resist God’s grace. Functionally, this “decision not to resist” is identical to a “work”. It puts the ball in the end in our court, not God’s. Our salvation depends on God, but it depends on us, too. My view is that, insofar as it depends on us, it depends on a “work”. Therefore it cannot depend on us. Therefore grace must be irresistible in order to be grace—in order for salvation to be by grace alone and not by grace plus works.

If faith is only given when the qualification of not resisting grace is met from our end, then to say that it is not a work is absurd—it misses the whole point of the radical soteriological emphasis on God’s action over and against our own action. Why would Paul spend so much time distinguishing faith and works if they are experienced functionally as almost identical? If the ball is to end up in our court after all?

(I am aware that, for the RCC, infusion potentially creates a way out here, at least for believer—because the changed will which “decides” is truly changed, by grace, and therefore is gracefully enabled not to resist God’s grace. If this is the case, however, then why does the RCC not agree that grace is irresistible?)

It is my view that Galatians is a polemic not against Pelagianism but against semi-Pelagianism. (Neither is it just against a random, no longer relevant 1st century discussion about circumcision and Jewish ethnic markers. To say that the view of the Law expressed by Paul in Galatians is reducible to a specific, no-longer-relevant discussion of whether and how Gentiles are saved is like saying Newton’s Laws of Motion only apply to apples falling from trees… But that’s another hobby horse).

There can be no mixing between our role and God’s role. As I quoted once before, “I testify again to every man who accepts circumcision that he is obligated to obey the whole law… A little leaven leavens the whole lump” (Gal. 6:3, 9).

I know that those of you who disagree with me will just say that I am wrong to equate their view of faith with a “work.” I disagree. If my salvation relies on my decision not to resist grace, then it relies on a work. I defy you to show otherwise! :)

Hence, irresistible grace. Mattie, this is the best I can do to answer your question, at least for myself, about the scriptural basis for irresistible grace.

PS- Do I get the award for the day for most time spent on John Camp that could have been spent doing other things? I know there are a lot of contenders ou there, but c'mon, you've got to give it to me...

Fantastic post Simeon.

Simeon-

quick question: where does the Holy Spirit fit into all of this? Meaning, in one-on-one pastoral situations, does being "lead by the spirit" to say something or what have you, ever fit into the equation?

While I agree completely with what you said in regards to "just" listening as opposed to semi-pelagian listening and/or ministering, isn't what you are suggesting in terms of forcing oneself to, essentially, "just" listen another form of Law?

I am new at this whole Gospel thing but I think that I really do get it. What trips me up, pastorally, is that, if we bring "nothing to the table" on our own, doesn't that imply that we are to just be vessels for which the Lord should use, if He chooses, in whatever capacity He chooses? The "just" listening thing seems more of a pragmatic tactic. For example, your insistence that we ought to force ourselves not to advise a person in any way, just listen, etc. during a ministry situation is much similar to, say, a PCA pastor's insistence that the way we ought to minister to a person should be through sharing scripture and holding someone accountable. Further, I thought that one of the main critiques of semi-pelagian theology is that it is "results" oriented and that this opposes the Gospel, which says that "results" or "fruit" are secondary, at best. But what you are saying is that "Augustinian"/ Lutheran/ non-semi-Pelagian method really works!" Is that why we should implement it? And even if, during these one-on-one situations, I don't judge the person verbally but am doing so on the inside, doesn't that negate my ability to truly love them? In short: is "doing nothing" in ministering situations just another form of Law? Where does the Holy Spirit fit in?

I would love to know your thoughts!

p.s. I guess, perhaps, the fact is that Augustinian pastoral care should be done just BECAUSE it works better, in the same way that reading the Bible and being in Fellowship should be done for the sake of survival (aka because it works, not because it justifies/sanctifies). In other words, maybe IT IS just another form of Law and that is fine and I just need to get over it since my enitre life is about the Law. I would still love your thoughts as I am wrestling with the theology behind all of this.

Simeon -

(Yes. Will here.)

A discursive ramble:

What you say about ministry of listening as avenue of grace sounds incredibly like my understanding of auricular confession. Ordination as grace comes with authority to forgive sins (cf. bcp 1662 ordinal "whosoever sins ye remit," etc.). The confessor becomes by grace an abyss of grace into which the penitent can toss his sins, with no fear of the tiniest fragment of them bouncing out. The only things he receives is release (absolution) and God's forgiveness. He doesn't hear anything but God's in the form of (1) the confessor's self-description ("I absolver you in the name of the Father, etc."), (2) an account of what has happened ("The Lord has put away your sins"), and (3) a command ("Go in peace, and pray...").

Lastly, I don't know what the RCC has said about the lutheran stuff, BUT. To return to my earlier point, I just can't see how grace's irresistibility does not entail limited atonement. If it is always iresistible, then the fact that some people aren't saved must be because they never received any grace. If they had received it, then they wouldn't have been able to resist it.

Note that we don't need access (as I said before) to God's inscrutibility to make this kind of argument. We only need access to the conceptual content of words like "saved" and "resist." And the assertion of the irresistibility of grace presumes that we DO have access to the conceptual content of these words. So it would not be fair to assert grace's irresistibility and then to pull the rug out from under someone asserting the entailment of Limited Atonement on the grounds that "we just don't know."

That would be my reason for not believing in the irresistibility. I can't see how it doesn't entail that God withholds his grace from certain of his creatures. Is this not what Calvin saw?

To lunch with DZ!

Dear Ben,

I think the "law" that simeon espouses is of another substance than works in that it is faith, that God is both listening and able to correct through the impact that love (something that cannot ever be produced genuinely by Law) has on the human heart in the context of struggle.

The scenario Simeon puts forth sounds much like the one Will understands as auricular confession. It also sounds a lot like the 5th step in AA. My hunch is that they are all indeed of the same breed. It also beautifully describes what I understand to be Repentance in its most down-to-earth sense. The sin is confessed, and the surprising/unexpected response that is found in God through Christ is grace, and particularly as it is expressed in that exact context of sin. Where this baffling response of God that is love is found, the heart cannot remain the same regarding the sin it has confessed. One breaks to the thing, first crying with guilt, then with joy. This is also imputation, pure and simple, the reckoning of a righteous status to the thing that deserves it not in such a way that a change of the infusion variety can actually occur, though, in those terms (infusion/ progress), it need never even be mentioned.

Simeon seemed to suggest that we can simply "do"/"practise" this approach. I think a more helpful way of putting forth the same idea would be to ask yourself to: "see how difficult and counterintuitive not offering a prescription in a counseling situation actually is". It can onlly occur as the product/substance of faith. Much harder than offering appropriately corrective suggestions, though they be (technically) absolutely spot on. I find it to be basically impossible to do the thing Sim is talking about, but to the extent that my natural tendency has been set free from the bondage of my own inclination, which is what I call fruit. As the beatle's say, "Can't Buy Me Love." In that sense it's not a law, but the gift of faith.

I really appreciated your question, and the calling to task of Simeon in the sense that his post was a bit misleading. I think what I'm really trying to say is that understanding what he said to be a law in the sense that it makes us aware of our own inability to adhere to the stringency of its standard enables us to realize just how righteous the thing Simeon DESCRIBES actually is. Without love, morality/righteousness is a clanging gong. Fortunately god's been working with contaminated motives on this exact front for a very long time. Best , JZ

Question to all:

Why do so many of us seem reluctant to subscribe to a doctrine of Limited Atonement? Is it because the Bible seems to contradict this idea, or because it offends our own human sense of what is fair?

Colton - Here's the Lutheran line on limited atonement & double predestination if it's helpful at all.

2) The nature of Christ's atonement. Lutherans believe that when Jesus died on the cross He atoned for the sins of all people of all time--even those who have not or will not come to faith in Christ. Reformed churches have historically taught a "limited atonement" of Christ, i.e., that Christ's death on the cross atoned only for the sins of "the elect"--those who have been predestined from eternity to believe in Christ and will spend eternity with Him in heaven.

3) Predestination. Most Reformed churches teach a "double predestination," i.e., that some people are predestined by God from eternity to be saved and others are predestined by God from eternity to be damned. Lutherans believe that while God in His grace in Christ Jesus has indeed chosen from eternity to save those who trust in Jesus Christ, He has not predestined anyone to damnation. Those who are saved are saved by grace alone; those who are damned are damned not by God's choice but because of their own sin and stubbornness. This is a mystery that is incomprehensible to human reason (as are all true Scriptural articles of faith).

Colton,

I think you nailed it. . . My understanding of Luther is that this very point is where you run up against the "whole chimichanga."

Tom. .

I agree that there are genuine differences between Lutheran and Reformed theology but I'm wondering where and how does Luther give any indication that he didn't believe in a functional "double predestination"? (I stress "functional" becaue I know later Lutheran dogmaticians rejected the terminology, but that terminology itself was a product of the late 16th century and not one Luther would have been familliar with)

again, I'll post just one of many quotes from "the Bondage of the Will". .

"Now, the highest degree of faith is to believe that He is merciful, though he saves so few and damns so many; to believe that He is just, though of His own will He makes us perforce proper subjects for damnation, and seems (in Erasmus’ words) to delight in the torments of poor wretches and to be a fitter object for hate than for love .

Colton,

I, for one, take issue with the idea of a 'limited atonement' not because of what it means for humanity, but what it means for Christ. Somehow, even though the term is not intended to mean this, it implies that Christ's death is less efficacious than it should have been.

Simeon,

Jady Koch made an absolutely brilliant point to me once about the difference between Calvin and Luther: Calvin talked about the elect, whereas Luther talked to them.

There are five key ideas at work. I am able to speak to the elect instead of about them because of...

1) The priesthood of all believers . The keys to the kingdom have not been given only to a set group of people. Roman Catholic apologists will often raise the issue of authority, and a popular example is a phone call to death row. You or I could ring that hotline all day long, but we are not the governor, so, despite our disagreement with the death penalty, we lack the authority to set the prisoner free.

A more Protestant view, however, might consider the Emancipation Proclamation as an example. Christ has generally proclaimed freedom to the captives, such that anyone has the authority to relay this message and demand the freedoms it implies.

Thus, you or I or anyone else is welcome to hear auricular confession and authoritatively grant absolution. I think Tim's point about sacramental confession is well-taken: the priest is required to forgive me when I confess my sin to him; my wife is not. True absolution occurs when I confess to someone I'm certain could never forgive me, and forgiveness is proclaimed to me because of Christ's sacrifice.

The overly liberal use of such a power is checked by the doctrine of...

2) Imputation . A person may not experience himself to be forgiven, but, if you treat him that way, he will come to believe it is true. Indeed, a person may not deserve to be forgiven, but that's precisely what grace is anyway.

One who does not hold to imputation must solicit a confession and an amendment of heart before granting forgiveness. You or I are free to "abuse" the keys and grant forgiveness to someone who hasn't earned it because we believe we are assigning to him something he doesn't deserve.

Thus can we pray the words of the prayer book, that we may be granted true repentance first and amendment of life second, but both only as part of the absolution itself, not as its predicate.

In operation with both of these is precisely the same principle that is at work in infant baptism, namely...

3) Vicarious faith . Until you can believe for yourself that your redemption is true, I will believe it for you, because its ultimately not based on what you want or do anyone, but rather on a proclamation that exists apart from you in which my faith already rests.

But doesn't this imply that I might impute salvation to someone who is not saved? No, because...

4) God desires that none should perish . If we believe that the forgiveness of sins is what causes repentance rather than vice-versa, then we can never forgive too many sins. Christ calls upon us to love and forgive everyone, and if amendment of life is a response to love rather than a predicate for it, then our loving, forgiving, and generally being "graceful" to others is one-in-the-same as imputation, the manner in which Protestants believe grace is given.

That is to say, our ministry really does have eternal consequences, and binding and loosing on earth and in heaven really is the best description for how living imputationally affects others and spreads the kingdom.

That last paragraph was the fifth point, incidentally.

Jeff,

(if I do say so myself) wonderful points. . and I'm definetly going to steal them and (possibly) cite you. .

In all of this discussion I want to underline Jeff's point and say that the idea of "limited atonement" is equally unacceptable to me due to the aforementioned implication that the Cross was insufficient for the "sins of the whole world". .

nonetheless, I think that the hard, cold, logically consistent position with a theology based upon the absence of "free will" is the terrifying reality of the God who saves. . . exactly how this works out, and the futility of explanation, can be found in the TULIP debates.

"Those who are saved are saved by grace alone; those who are damned are damned not by God's choice but because of their own sin and stubbornness."

Being damnably sinful and stubborn sounds a lot like successfully resisting grace.

Why are we so resistant to the notion of Limited Atonement? I resist it because I cannot separate the grace of God from the love of God -- I don't think divine grace and divine love are different. And I cannot see God as not loving some of his creatures. That too is why I cannot believe that grace is irresistible - though I hope that it is (because I hope that all will be redeemed in the end, though it doesn't look like that will be the case).

That is, I can't make sense of such dicta as "God is love" and "God so love the world..." and "he is the perfect offering... for the sins of the whole world" in such a way as to make them compatible with God not loving certain of his creatures (i.e. the damned ones).

Also: what's the problem with something's being prescribed? Jesus prescribed all kinds of things. Preach the gospel, go in peace, sin no more, baptize, make disciples, fear not, do this, etc. etc. etc.

Dear Will,

the short answer to your question on prescription usually runs along the following lines: Prescription does not provide a method for bringing about the thing it requires, but, rather (to quote Romans 7) it "increases the trespass," "making sin utterly sinful". It tells the car where to go, but it doesn't put any gas in the tank.

Where there is prescription, there immediately comes the opposite of the thing the prescription intended, and this is what it means for the will to be bound. Knowing better does not equal doing better according to Paul (foolishness to the Greeks), and, if anything, it increases the doing of worse, or, at a minimum, puts the doing of "worse" into the perspective of not being as good as the standard fulfilled.

So the Law (as prescription) brings rebellion and penitance. Paul calls this "the proper use of the law" in 1 Timothy 1: 8, 9. Jesus further clarifies the law in the Sermon on the Mount in his antitheses, by showing that prescription exposes an impossible angling of the heart, one that mere behavioral adherence cannot meet the standard of (i.e., suddenly adultery is not a behavior, but a motive, etc. That portion of the Sermon on the Mount climaxes with: be ye perfect therefore as your Father in heaven is perfect -- good luck!) -- This exact issue is currently being discussed on in the thread under the post called "An Insight from Jeff Dean"; it's a far from settled hermeneutical matter, but what I describing here is the basic sort of Luther 101 position on the matter. I hope those of you who are sympathetic to such a read, can help me to tighten this us if you think I've gone far astray here.

Anway, as a result of this awful conundrum known as the human condition post-Fall,...(drum roll) "thanks be to Jesus Christ" who died to on the behalf of us sinners who know ourselves as sinners in light of the fact that we cannot set the record straight in the way the Law demands through our own efforts (i.e., works based righteousness), and God cannot commune with anything less. According to this view, prescription is always basically a big set-up for "repent and believe the Gospel".

If Jesus' command, and any other commandments in the Bible (especially given the nature of human reception of any kind of command as illuminated by Paul in Romans 7 famously) could simply be followed in the way that their imperative nature requires, then why did Jesus have to die, and so brutally at that? In what sense is Grace really grace, and forgiveness really forgiveness and mercy really mercy and love really love if those qualities are not a response to something that requires them? In the same vein, tolerance and love are obviously not the same thing.

Furthermore, if the law can be fulfilled by us, then the Bible often starts to be interpreted as a rule book of some sort, a ladder for us to climb (rather than the story of one who came down and then climbed up on our behalf while we were busy doing our own thing).

Obviously, for those who buy into this read of prescription, the implications are pretty major for how you come to understand the Christian life; the Gospel has to do with a lot more than just conversion, it also has to do with sanctification. Salvation and sanctification become seemingly identical in the view of some. The message one preaches to the Christian is no different than the message one preaches to the non-Christian.

Some Christians try to draw different distinctions as to just how far-reaching the implications of this understanding travel. Does this relationship to the Law altar at the point of conversion? Calvin says yes. Most Christians say yes. Luther appears (at least in his notable Commentary on Galatians, which is the thing that Wesley was listening to when his heart was "strangely warmed") to basically say "No", though that's been well disputed. W. Elert argues strongly against any other interpretation of Luther, and makes for a pretty fun read. My favorite, shared by many, is Gerhard Forde's "On Being a Theologian of the Cross". It is short and really worth reading. I can't plug it enough. Others try to draw lines between different kinds of prescription, that some can be adhered to, while others can't. It's basically the history of Protestant denominational break-down.

The most commonly lobbed criticism of this view that Prescription only works in this strange back-handed manner is "antinomianism", which suggests that being set free from the Law's prescriptive quality through Christ's Cross results in dangerous anarchic freedom, and of the most immoral kind at that. This criticism was not stranger to Paul himself: "Should we sin more that grace may abound?"